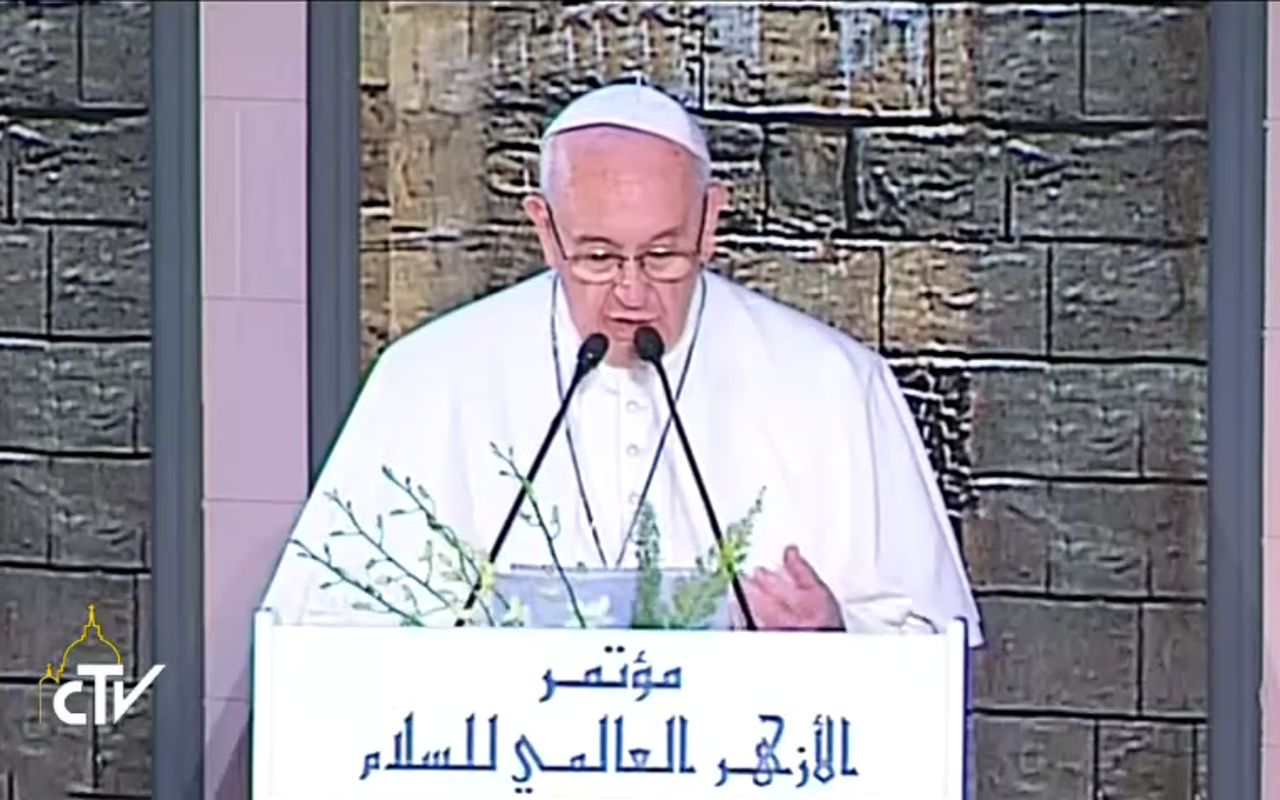

As-salamu alaykum! Peace be with you!

I consider it a great gift to be able to begin my Visit to Egypt here, and to address you in the context of this International Peace Conference. I thank the Grand Imam for having planned and organized this Conference, and for kindly inviting me to take part. I would like to offer you a few thoughts, drawing on the glorious history of this land, which over the ages has appeared to the world as a land of civilizations and a land of covenants.

A land of civilizations

From ancient times, the culture that arose along the banks of the Nile was synonymous with civilization. Egypt lifted the lamp of knowledge, giving birth to an inestimable cultural heritage, made up of wisdom and ingenuity, mathematical and astronomical discoveries, and remarkable forms of architecture and figurative art. The quest for knowledge and the value placed on education were the result of conscious decisions on the part of the ancient inhabitants of this land, and were to bear much fruit for the future. Similar decisions are needed for our own future, decisions of peace and for peace, for there will be no peace without the proper education of coming generations. Nor can young people today be properly educated unless the training they receive corresponds to the nature of man as an open and relational being.

Education indeed becomes wisdom for life if it is capable of 'drawing outâ? of men and women the very best of themselves, in contact with the One who transcends them and with the world around them, fostering a sense of identity that is open and not self-enclosed. Wisdom seeks the other, overcoming temptations to rigidity and closed-mindedness; it is open and in motion, at once humble and inquisitive; it is able to value the past and set it in dialogue with the present, while employing a suitable hermeneutics. Wisdom prepares a future in which people do not attempt to push their own agenda but rather to include others as an integral part of themselves. Wisdom tirelessly seeks, even now, to identify opportunities for encounter and sharing; from the past, it learns that evil only gives rise to more evil, and violence to more violence, in a spiral that ends by imprisoning everyone. Wisdom, in rejecting the dishonesty and the abuse of power, is centred on human dignity, a dignity which is precious in Godâ??s eyes, and on an ethics worthy of man, one that is unafraid of others and fearlessly employs those means of knowledge bestowed on us by the Creator.1

Precisely in the field of dialogue, particularly interreligious dialogue, we are constantly called to walk together, in the conviction that the future also depends on the encounter of religions and cultures. In this regard, the work of the Mixed Committee for Dialogue between the Pontifical Council for Interreligious Dialogue and the Committee of Al-Azhar for Dialogue offers us a concrete and encouraging example. Three basic areas, if properly linked to one another, can assist in this dialogue: the duty to respect oneâ??s own identity and that of others, the courage to accept differences, and sincerity of intentions.

The duty to respect oneâ??s own identity and that of others, because true dialogue cannot be built on ambiguity or a willingness to sacrifice some good for the sake of pleasing others. The courage to accept differences, because those who are different, either culturally or religiously, should not be seen or treated as enemies, but rather welcomed as fellow-travellers, in the genuine conviction that the good of each resides in the good of all. Sincerity of intentions, because dialogue, as an authentic expression of our humanity, is not a strategy for achieving specific goals, but rather a path to truth, one that deserves to be undertaken patiently, in order to transform competition into cooperation.

An education in respectful openness and sincere dialogue with others, recognizing their rights and basic freedoms, particularly religious freedom, represents the best way to build the future together, to be builders of civility. For the only alternative to the civility of encounter is the incivility of conflict. To counter effectively the barbarity of those who foment hatred and violence, we need to accompany young people, helping them on the path to maturity and teaching them to respond to the incendiary logic of evil by patiently working for the growth of goodness. In this way, young people, like well-planted trees, can be firmly rooted in the soil of history, and, growing heavenward in one anotherâ??s company, can daily turn the polluted air of hatred into the oxygen of fraternity.

In facing this great cultural challenge, one that is both urgent and exciting, we, Christians, Muslims and all believers, are called to offer our specific contribution: 'We live under the sun of the one merciful God... Thus, in a true sense, we can call one another brothers and sisters... since without God the life of man would be like the heavens without the sunâ?.2 May the sun of a renewed fraternity in the name of God rise in this sun-drenched land, to be the dawn of a civilization of peace and encounter. May Saint Francis of Assisi, who eight centuries ago came to Egypt and met Sultan Malik al Kamil, intercede for this intention.

A land of covenants

In Egypt, not only did the sun of wisdom rise, but also the variegated light of the religions shone in this land. Here, down the centuries, differences of religion constituted 'a form of mutual enrichment in the service of the one national communityâ?.3 Different faiths met and a variety of cultures blended without being confused, while acknowledging the importance of working together for the common good. Such 'covenantsâ? are urgently needed today. Here I would take as a symbol the 'Mount of the Covenantâ? which rises up in this land. Sinai reminds us above all that authentic covenants on earth cannot ignore heaven, that human beings cannot attempt to encounter one another in peace by eliminating God from the horizon, nor can they climb the mountain to appropriate God for themselves (cf. Ex 19:12).

This is a timely reminder in the face of a dangerous paradox of the present moment. On the one hand, religion tends to be relegated to the private sphere, as if it were not an essential dimension of the human person and society. At the same time, the religious and political spheres are confused and not properly distinguished. Religion risks being absorbed into the administration of temporal affairs and tempted by the allure of worldly powers that in fact exploit it. Our world has seen the globalization of many useful technical instruments, but also a globalization of indifference and negligence, and it moves at a frenetic pace that is difficult to sustain. As a result, there is renewed interest in the great questions about the meaning of life. These are the questions that the religions bring to the fore, reminding us of our origins and ultimate calling. We are not meant to spend all our energies on the uncertain and shifting affairs of this world, but to journey towards the Absolute that is our goal. For all these reasons, especially today, religion is not a problem but a part of the solution: against the temptation to settle into a banal and uninspired life, where everything begins and ends here below, religion reminds us of the need to lift our hearts to the Most High in order to learn how to build the city of man.

To return to the image of Mount Sinai, I would like to mention the commandments that were promulgated there, even before they were sculpted on tablets of stone.4 At the centre of this 'decalogueâ?, there resounds, addressed to each individual and to people of all ages, the commandment: 'Thou shalt not killâ? (Ex 20:13). God, the lover of life, never ceases to love man, and so he exhorts us to reject the way of violence as the necessary condition for every earthly 'covenantâ?. Above all and especially in our day, the religions are called to respect this imperative, since, for all our need of the Absolute, it is essential that we reject any 'absolutizingâ? that would justify violence. For violence is the negation of every authentic religious expression.

As religious leaders, we are called, therefore, to unmask the violence that masquerades as purported sanctity and is based more on the 'absolutizingâ? of selfishness than on authentic openness to the Absolute. We have an obligation to denounce violations of human dignity and human rights, to expose attempts to justify every form of hatred in the name of religion, and to condemn these attempts as idolatrous caricatures of God: Holy is his name, he is the God of peace, God salaam.

Peace alone, therefore, is holy and no act of violence can be perpetrated in the name of God, for it would profane his Name. Together, in the land where heaven and earth meet, this land of covenants between peoples and believers, let us say once more a firm and clear 'No!â? to every form of violence, vengeance and hatred carried out in the name of religion or in the name of God. Together let us affirm the incompatibility of violence and faith, belief and hatred. Together let us declare the sacredness of every human life against every form of violence, whether physical, social, educational or psychological. Unless it is born of a sincere heart and authentic love towards the Merciful God, faith is no more than a conventional or social construct that does not liberate man, but crushes him. Let us say together: the more we grow in the love of God, the more we grow in the love of our neighbour.

Religion, however, is not meant only to unmask evil; it has an intrinsic vocation to promote peace, today perhaps more than ever.6 Without giving in to forms of facile syncretism,7 our task is that of praying for one another, imploring from God the gift of peace, encountering one another, engaging in dialogue and promoting harmony in the spirit of cooperation and friendship. For our part, as Christians, 'we cannot truly pray to God the Father of all if we treat any people as other than brothers and sisters, for all are created in Godâ??s imageâ?.8 Moreover, we know that, engaged in a constant battle against the evil that threatens a world which is no longer 'a place of genuine fraternityâ?, God assures all those who trust in his love that 'the way of love lies open to men and that the effort to establish universal brotherhood is not vainâ?.9 Rather, that effort is essential: it is of little or no use to raise our voices and run about to find weapons for our protection: what is needed today are peacemakers, not fomenters of conflict; firefighters and not arsonists; preachers of reconciliation and not instigators of destruction.

It is disconcerting to note that, as the concrete realities of peopleâ??s lives are increasingly ignored in favour of obscure machinations, demagogic forms of populism are on the rise. These certainly do not help to consolidate peace and stability: no incitement to violence will guarantee peace, and every unilateral action that does not promote constructive and shared processes is in reality a gift to the proponents of radicalism and violence. In order to prevent conflicts and build peace, it is essential that we spare no effort in eliminating situations of poverty and exploitation where extremism more easily takes root, and in blocking the flow of money and weapons destined to those who provoke violence. Even more radically, an end must be put to the proliferation of arms; if they are produced and sold, sooner or later they will be used. Only by bringing into the light of day the murky manoeuvrings that feed the cancer of war can its real causes be prevented. National leaders, institutions and the media are obliged to undertake this urgent and grave task. So too are all of us who play a leading role in culture; each in his or her own area, we are charged by God, by history and by the future to initiate processes of peace, seeking to lay a solid basis for agreements between peoples and states. It is my hope that this noble and beloved land of Egypt, with Godâ??s help, may continue to respond to the calling it has received to be a land of civilization and covenant, and thus to contribute to the development of processes of peace for its beloved people and for the entire region of the Middle East.

As-salamu alaykum! Peace be with you!

__________________________________________________

1 'An ethics of fraternity and peaceful coexistence between individuals and among peoples cannot be based on the logic of fear, violence and closed-mindedness, but on responsibility, respect and sincere dialogueâ?: Nonviolence: a Style of Politics for Peace, Message for the 2017 World Day of Peace, 5.

2 JOHN PAUL II, Address to Muslim Religious Leaders, Kaduna (Nigeria), 14 February 1982.

3 John Paul II, Address at the Arrival Ceremony, Cairo, 24 February 2000.

4 'They were written on the human heart as the universal moral law, valid in every time and place. Today as always, the Ten Words of the Law provide the only true basis for the lives of individuals, societies and nations. [...] They are the only future of the human family. They save man from the destructive force of egoism, hatred and falsehood. They point out all the false gods that draw him into slavery: the love of self to the exclusion of God, the greed for power and pleasure that overturns the order of justice and degrades our human dignity and that of our neighbourâ? (John Paul II, Homily during the Celebration of the Word at Mount Sinai, Saint Catherineâ??s Monastery, 26 February 2000).

5 Address at the Central Mosque of Koudoukou, Bangui (Central African Republic), 30 November 2015.

6 'More perhaps than ever before in history, the intrinsic link between an authentic religious attitude and the great good of peace has become evident to allâ? (JOHN PAUL II, Address to Representatives of the Christian Churches and Ecclesial Communities and of the World Religions, Assisi, 27 October 1986: Insegnamenti IX, 2 (1986), 1268.

7 Cf. Apostolic Exhortation Evangelii Gaudium, 251.

8 SECOND VATICAN ECUMENICAL COUNCIL, Declaration Nostra Aetate, 5.

9 ID., Pastoral Constitution Gaudium et Spes, 38.